Jimmy Simpson Sr. - The Life and Legacy of a Mountain Legend

- whytemuseum

- Jan 26, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: May 18, 2023

By Kate Riordon, Collections Processor & Digital Technician

A pioneer of guiding and outfitting in the Canadian Rockies and founder of Num-Ti-Jah Lodge, Jimmy Simpson Sr. is a household historical name - thanks to hard work and humble beginnings.

Reputations are a funny thing. If I told you to picture a man who guided climbing and hunting trips on horseback for 40 years, worked as a camp cook for mountaineers like A.O. Wheeler and Edward Whymper in the early 1900s, and built a hotel in the middle of nowhere by himself, what would he look like?

I’m willing to bet you aren’t picturing a short, wiry, red-haired Scot. Like many who heard about James “Jimmy” Simpson prior to meeting him, you aren’t alone.

![Jimmy Simpson with dog, [ca. 1905], Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 01, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_7d1e512186f84461b7a27631499f4a7f~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_679,h_1000,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_7d1e512186f84461b7a27631499f4a7f~mv2.jpg)

Born Justin James McCarthy Simpson in 1877 in Scotland, Jimmy (as he was quickly nicknamed), left the country of his birth before his 20th birthday and never went back. Reports differ on how old he was when he left, but it’s largely agreed that the reason for his migration was that he embarrassed his family by laughing in church. His path to the Rockies wasn’t exactly a smooth one, either. After spending a solid 24 hours on a farm south of Winnipeg, Jimmy figured anything had to be better than that, and he kept moving west. In Calgary, he ran into some boys he’d met while at a boarding house in Winnipeg and, despite not having a ticket, joined them on their trainride into the mountains. To hear him tell it, Jimmy was kicked off the train at Silver City (a long-gone mining town at the base of Castle Mountain) for “snoring too loudly” inside the berth he’d been hiding in.[1] From there he walked 29 kilometres (18 miles) to Laggan.

An Outfitter is Born

Laggan, called Lake Louise today, turned out to be a very hospitable place for young Jimmy. By 1897, he was working for legendary outfitter Tom Wilson, who had also employed Fred Stephens and Bill Peyto at the beginnings of their respective careers.[2] Jimmy, with little in the way of experience on the trail but an excess in the way of enthusiasm, began paying his dues by slinging grub as the camp cook. Despite his diminutive size and low station in the outfitting pecking order, Jimmy was quick and strong and had a way with both people and horses — it wasn’t long before he left Wilson’s employ to strike out on his own. By 1906, Jimmy had worked for both Tom Wilson and Bill Peyto, had had two different business partners, and now operated out of Banff as a solo outfitter. In the years leading up to World War I, his biggest competitors were none other than Jim and Bill Brewster, founders of the Brewster Transportation empire.

![Right – Jimmy Simpson. Porch of Banff Springs Hotel ; trip to Red Earth Creek with Joe Woodworth [detail], [ca. 1915], Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / I / A / 2 / B / PS 2 – 63, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_00c65a19a50f4a82ac51eb87e5aa9182~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_485,h_514,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_00c65a19a50f4a82ac51eb87e5aa9182~mv2.jpg)

Life in Banff suited Jimmy fine enough. His reputation had spread so that he was usually able to fill his warm months packing climbers and hunters throughout the park, and he filled his winters coaching hockey, promoting the Banff Curling Club, and working his traplines with Fred Ballard. He and Fred made for an interesting pair. While Jimmy was so skilled in travelling on snowshoes that the Stoney Nakoda named him Nashan-esen (Wolverine-go-quickly), Fred once held a pair of his shoes at gunpoint because they made him slip and fall head-first into a pile of logs.[3]

![Jimmy Simpson (on horse left) and Fred Ballard (on horse right) on a trapping trip, [ca. 1900], George Paris fonds, V484 / 1245 / na66 – 2075, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_b5558e83fe2649d08283507796e4f978~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_781,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_b5558e83fe2649d08283507796e4f978~mv2.jpg)

The Protégé of a Painter

Jimmy was a mountain man through and through. Like many of his contemporaries, he loved whiskey, hunting (especially mountain sheep), trapping, and trying to stay one step ahead of the government. But did you know he also loved to paint? Like all good lads of a certain generation, Jimmy had “learned the skills of a British amateur naturalist,” and in 1910 he finally got to test those skills when he invited renowned wildlife painter Carl Rungius to come visit.[4] Rungius, who initially threw Jimmy’s letter of invitation in the trash, turned out to be a mentor born of opportunity and, inevitably, a lifelong friend.

![Carl Rungius with net, [ca. 1920], Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 499, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_2e6eb1b906b840018b270b99f888e68a~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_686,h_1000,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_2e6eb1b906b840018b270b99f888e68a~mv2.jpg)

Together, the two men roamed the regions of the Rocky Mountains most likely to harbour large game, hunting both with rifles and cameras. Rungius’ style and use of colour fascinated Jimmy, who already knew his way around a set of watercolour paints, and his influence is obvious in Jimmy’s work. Over the next decade, Jimmy became busier running his outfitting business and didn’t have as much time to go out hunting with Rungius. Luckily, Rungius now had a house and studio on Cave Avenue in Banff and was largely able to navigate the park without a guide – although he did still hire pack hands and gear from Jimmy in exchange for paintings.

In 1916, Jimmy added another title to his already impressive list of descriptive terms: husband. That year, he married Williamina “Billie” Ross Reid and, just one year later, they welcomed their first daughter, Margaret.

If you think family life was able to slow Jimmy Simpson down, I regret to inform you that you’re mistaken.

The Next Chapter at Num-Ti-Jah Lodge

In 1922, now with two daughters and a newborn son in tow (Mary joined the brood in 1919 and little Jimmy Jr. came along in 1922), Jimmy started on the project that would stand as his longest-lasting contribution to Banff National Park. Approved for the lease of five acres of land along the shore of Bow Lake, Jimmy started construction on Num-Ti-Jah Lodge, a small, octagonal log cabin to be used mostly by his horseback trips — the unusual shape of the building was in owing to the fact that the trees in that area were so short.[5] This cabin served as the launching point for many of his outfitting trips. From Banff, parties would take the train to Lake Louise and then head on horseback to Bow Lake. Like the high alpine climbing huts that served mountaineers, Jimmy’s small lodge served as a comfortable waystation for his guests.

![Original Num-Ti-Jah Lodge, [ca. 1955], George Noble fonds, V469 / 1001, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_d12e1820a401447888cb4edb767b8e9b~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_673,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_d12e1820a401447888cb4edb767b8e9b~mv2.jpg)

The dominance of horseback travel wasn’t long for the world though. The Brewsters’ successes in tourism and transportation saw the rise of the automobile throughout Canadian National Parks in the interwar years. In 1933, the government began construction on the Banff-Jasper Highway, running a road conveniently close to Jimmy’s remote lodge. Smelling money along with all that tar, Jimmy began building a proper lodge alongside his original cabin in 1937. This bigger building featured 24 guest rooms, a parlour, a dining room, and nearby stables for the horses Jimmy still used for day and overnight trips.

![Num-Ti-Jah Lodge, [ca. 1955], George Noble fonds, V469 / 1002, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_253a3b7fc7dd4eb68c8df71f82408530~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_785,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_253a3b7fc7dd4eb68c8df71f82408530~mv2.jpg)

Billie oversaw the majority of the day-to-day running of the lodge and Jimmy continued to guide parties (usually hunting) well into the 1940s. It wasn’t until after World War II that Jimmy began turning complete control of his business — lodging and guiding — over to his son. In a move that feels very full circle, Jimmy acted as camp cook for some of these later trips well into his 70s.

A Conversation Craftsman

Jimmy Simpson was a compelling man. While he never graduated high school nor attended university, he had a keen mind and a sharp intellect. In order to effectively entertain whomever he was guiding, he would read up on their favourite topics so they would have common ground to share on the trail. He also had a flair for showmanship and kept his guests, employees, partners, family, and — probably most of all — himself entertained with all manner of jokes, both practical and otherwise. He possessed what my father would call “the gift of the gab” and had a penchant for spinning yarns. Which is more than a little impressive when you remember that he did all this talking with a pipe clamped firmly between his teeth.

![The Simpson family at Num-Ti-Jah [Mary & Jimmy Jr. standing, Billie & Jimmy Sr. seated], Aug 10 1956, Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 95, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_15cbd65b24d84f038a76e8750afa2371~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_757,h_1000,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_15cbd65b24d84f038a76e8750afa2371~mv2.jpg)

![Jimmy Simpson with pipe, [ca. 1965], Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 19, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_a50703faabc241a387bad5328e40af6b~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_710,h_1000,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_a50703faabc241a387bad5328e40af6b~mv2.jpg)

Even in the recorded interviews he did with Catharine Robb Whyte in the 1950s, you can hear the scratch of matches being struck and the faint whistling of when he’d pull on the pipe. Jimmy and Catharine (as well as their spouses) shared a lot in common and had been friends since the Whytes settled in Banff in the early 1930s, even despite the fact that the Simpsons were old enough to be Peter and Catharine’s parents. In 1968, Catharine granted Jimmy and sculptor Charlie Biel the honour of cutting the rawhide strip that officially opened the original Whyte Museum building.

Interview with Jimmy Simpson and Catharine Robb Whyte.

Jimmy passed away in 1972 at the age of 95, joining Billie and, tragically, Margaret. Over the better part of the 80 years Jimmy lived in the Canadian Rockies, he walked the trails with the likes of Tom Wilson, Hector Crawler, “Wild” Bill Peyto, and Sid Unwin. He played host to artists, botanists, geologists, climbers, hunters, and even a wealthy widow with a penchant for collecting rare butterflies.[6]

![Jimmy Simpson, [ca. 1965], Bruno Engler, photographer, Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 21, Archives & Special Collections](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/cd2968_a0aaffa9448647c1b0a6ea193e50c02f~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_837,h_1000,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/cd2968_a0aaffa9448647c1b0a6ea193e50c02f~mv2.jpg)

Yes, he had a truly staggering reputation, but he never grew very tall.

To learn more about the life and works of Jimmy Simpson, visit our current exhibition at the Whyte Museum in the Heritage Gallery, explore the Lizzie Rummel room for reading on Canadian Rockies history, or book an appointment with the Whyte Museum Archives.

Images

Image 1: Jimmy Simpson with dog, [ca. 1905], Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 01, Archives & Special Collections

Image 2: Left – Jimmy Simpson. Porch of Banff Springs Hotel ; trip to Red Earth Creek with Joe Woodworth [detail], [ca. 1915], Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / I / A / 2 / B / PS 2 – 63, Archives & Special Collections

Image 3: Jimmy Simpson (on horse left) and Fred Ballard (on horse right) on a trapping trip, [ca. 1900], George Paris fonds, V484 / 1245 / na66 – 2075, Archives & Special Collections

Image 4: Ptarmigan Pass hunting trip, 1920, Byron Harmon, photographer, Byron Harmon fonds, V263 / NA – 529, Archives & Special Collections

Image 5: Carl Rungius with net, [ca. 1920], Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 499, Archives & Special Collections

Image 6: Carl Clemens Moritz Rungius (1869 – 1959, American), In the Ogilvie Rockies, [ca. 1940], oil on canvas, 74.5 x 100.5 cm, Collection of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Gift of Anne Harbison, RuC.02.15

Image 7: James (Sr.) Simpson (1975 – 1972, Canadian), Untitled [Mountain Pass], 1948, watercolour on paper, 15.1 x 20.3 cm, Collection of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Gift of Lillian Gest, SiJ.05.45

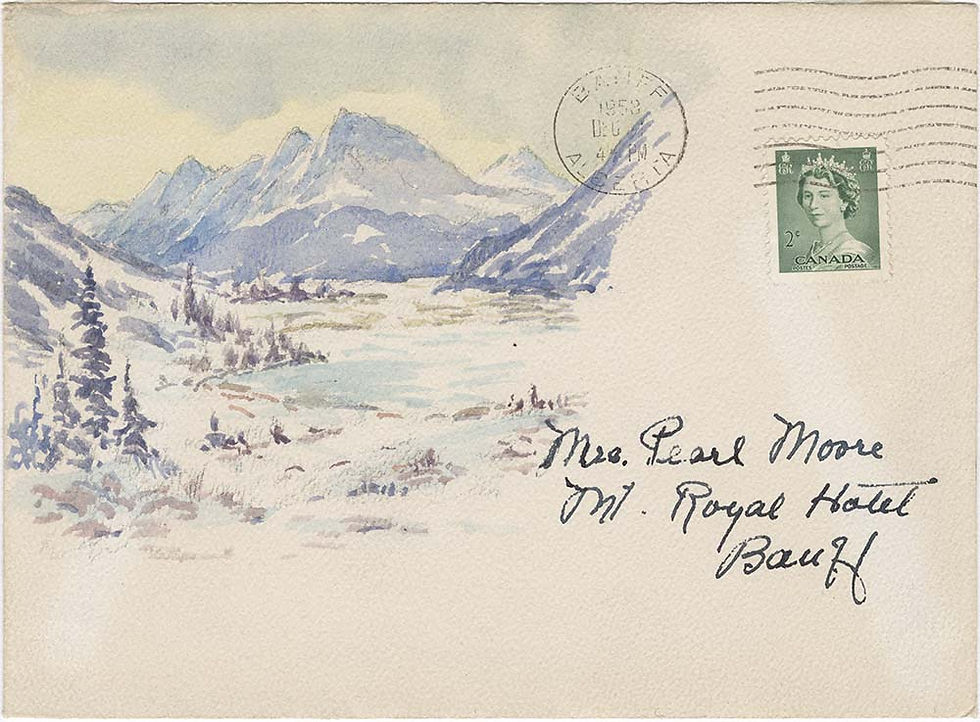

Image 8: James (Sr.) Simpson (1975-1972, Canadian), Untitled [Mountain Scene], 1958, watercolour on paper, 9.0 x 12.0 cm, Collection of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Gift of Pearl Evelyn Moore, SiJ.05.14

Image 9: Original Num-Ti-Jah Lodge, [ca. 1955], George Noble fonds, V469 / 1001, Archives & Special Collections

Image 10: Num-Ti-Jah Lodge, [ca. 1955], George Noble fonds, V469 / 1002, Archives & Special Collections

Image 11: The paddock that Jimmy built still partially stands not far from Bow Lake, September 2022, photo by author

Image 12: The Simpson family at Num-Ti-Jah [Mary & Jimmy Jr. standing, Billie & Jimmy Sr. seated], Aug 10 1956, Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 95, Archives & Special Collections

Image 13: Jimmy Simpson with pipe, [ca. 1965], Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 19, Archives & Special Collections

Image 14: Jimmy Simpson & Charlie Biel at the opening ceremony of the Whyte Museum, 1968, Peter & Catharine Whyte fonds, V683 / I / B / 1 / PA – 854, Archives & Special Collections

Image 15: Jimmy Simpson, [ca. 1965], Bruno Engler, photographer, Jimmy Simpson family fonds, V577 / II / D / PA – 21, Archives & Special Collections

Endnotes:

[1] Interview with Jimmy Simpson Sr. track 2, 30 May, 1952, S37 / 18, Peter & Catharine Robb Whyte fonds, Whyte Museum Archives & Special Collections [2] “Diamond Hitch: The Early Outfitters and Guides of Banff and Jasper,” E.J. Hart, 1979, Summerthought, pg. 46 [3] Ibid, pg. 70 [4] “Carl Rungius: Painter of the Western Wilderness,” Jon Whyte & E.J. Hart, 1985, Glenbow-Alberta Institute, pg. 79 [5] “Diamond Hitch,” E.J. Hart, pg. 137 [6] Ibid, pg. 119

Comments