By Kate Riordon, Archival Assistant

An amateur, as defined by Meriam-Webster, is “someone who engages in a pursuit, study, science, or sport as a pastime rather than as a profession.” There is a slight stigma placed on the word “amateur” – it sounds like an insult, like the person is incompetent in some way, which is a pretty harsh critique. When it came to photographers in the 20th century though, it was a common – and respected – title.

[Unidentified man and George X Vaux], [ca.1930], Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, George Vaux X fonds (V654/I/A/PA–1055)

[Leonard Leacock], [ca.1945], Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies,

Leacock family fonds (V352/PA–1)

Both George X Vaux and Leonard Leacock were self-professed amateur photographers and both achieved a fair level of acclaim in the field of photography throughout their lives. Their backgrounds, methods, and motivations varied, but they were united by their amateur status and their love for the wild places of the mountains. I learned this about them while working on the digital exhibit, Illuminating Lantern Slides, and I admit I became a bit obsessed. Here, I aim to explore the heights to which these amateurs climbed in order to record and share the mountains they loved.

In order to get an idea of the environment which George X Vaux grew up in, it is important to understand where his family came from. George X was born in 1909 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where his family had been living for five generations since moving from England to Philadelphia to escape persecution for their religious beliefs. The Vaux family were Quakers, a Christian-based religion that emphasizes a personal, loving relationship with God and placing high value in people and their inherent goodness. Quakers believe that people, not necessarily just their souls, are most important and some of the cornerstones of the religion are community and human rights. They valued simplicity over all: math, sciences, law, and medicine were all “acceptable” trades or pastimes, while things like art, literature, music, and dance were frivolous and vain.

George X Vaux’s father (George IX Vaux), aunt (Mary Vaux Walcott), and uncle (William Vaux Jr.) had adopted more liberal stances within their faith, possibly a result of growing up in the immediate wake of the Industrial Revolution. The aftermath of industrialization saw the rise of the amateur alongside the new technologies. With no real standard for what constituted a “professional,” people who took up activities like photography naturally became amateurs. George X’s father, aunt, and uncle were able to express themselves artistically through photography by displaying their pictures in the context of geographical and environmental study. Photography to this day is a grey area used for artistic, documentary, and scientific purposes and people in the 1800s kept busy arguing over which had the stronger claim.

On Burgess Pass, [Henry J.] Vaux, G. Vaux, Mary Vaux Walcott, [ca. 1934], Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, George Vaux X fonds (V654/I/A/PS–25)

Mary M. Vaux, George Vaux, William S. Vaux, 1908, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Vaux family fonds (V653/I/2/PA–1) From left to right: George X’s aunt, father, and uncle

By the time George X started coming to the Canadian west in 1927, his father, aunt, and uncle were respected fixtures when it came to photography. Their artistic talent as well as their dedication to recording the local environment was more than enough to garner them public interest and acclaim. While George X’s father, aunt, and uncle often displayed their photographs in lectures and galleries, they never actively sought to sell them, maintaining their amateur status. This likely influenced George X to do the same – he worked as an engineer in Philadelphia and maintained photography as a pastime.

George X Vaux was born in the early years of the 1900s and grew up during a time when photographic technology was bounding ahead at breakneck speeds. When George X’s father, aunt, and uncle visited Alberta and British Columbia in the late 1800s and early 1900s the cameras they used were large, heavy, and used glass or metal plates to take exposures. By the time of his first visit to the Canadian Rockies in 1927, celluloid-based film was becoming the more popular option over glass plates and the cameras were becoming smaller and lighter. George X was not immune to changing preferences in photographic mediums. The collection of lantern slides from his trip in summer 1939 are full colour celluloid film photographs mounted within glass casings. Not only had George X embraced new technologies, he bucked the extremely popular practice of black and white photography favoured by professional photographers.

View of Lake Louise and Victoria Glacier with table, chairs, and umbrella,1939, George Vaux X/photographer, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies,

George Vaux X fonds (V654/I/E/ PS–15)

Beginnings of Healy Creek, 1925-1931, Leonard Leacock/photographer, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Leonard Leacock fonds (V353/I/B/PS–112)

Considering his family’s history with photography, George X’s embrace of new technologies is not very surprising, but the use of colour film prior to the 1960s is a bit more unusual. Even though colour photography was commercially available as early as 1907, it did not gain widespread popularity until well into the latter half of the 20th century.

Leonard Leacock also favoured coloured pictures, but unlike George X, when it came to lantern slides, Leonard employed a fully glass slide, rather than encasing a film insert between glass panes. Leonard was also a natural mountaineer. Born in 1904 and moving to Banff at the age of four in 1908, he grew up exploring the forests, hills, and lakes of the National Park. Leonard’s choices for his lantern slides may have been the more traditional for the time during which he was taking these pictures (the collection housed in the Archives are dated from 1925-1931), but his use of glass struck me as strange for another reason. Leonard often stated in interviews that he loved travelling on foot in the mountains and even if horses were an option, he often chose to walk. The thought of having to carry glass negatives along with rolls of film, the camera and its equipment, and everything else one brings on a hike does not sound like my idea of a good time. It certainly would not be impossible, but not my first choice. It may not have been Leonard’s either – he possibly developed the glass positives from film negatives for his lantern slides.

Leonard Leacock used the box on the right to store his finished lantern slides in. Lined with felt, these boxes could safely hold about 85 slides. The archival boxes on the left each hold 40 of Leacock’s slides.

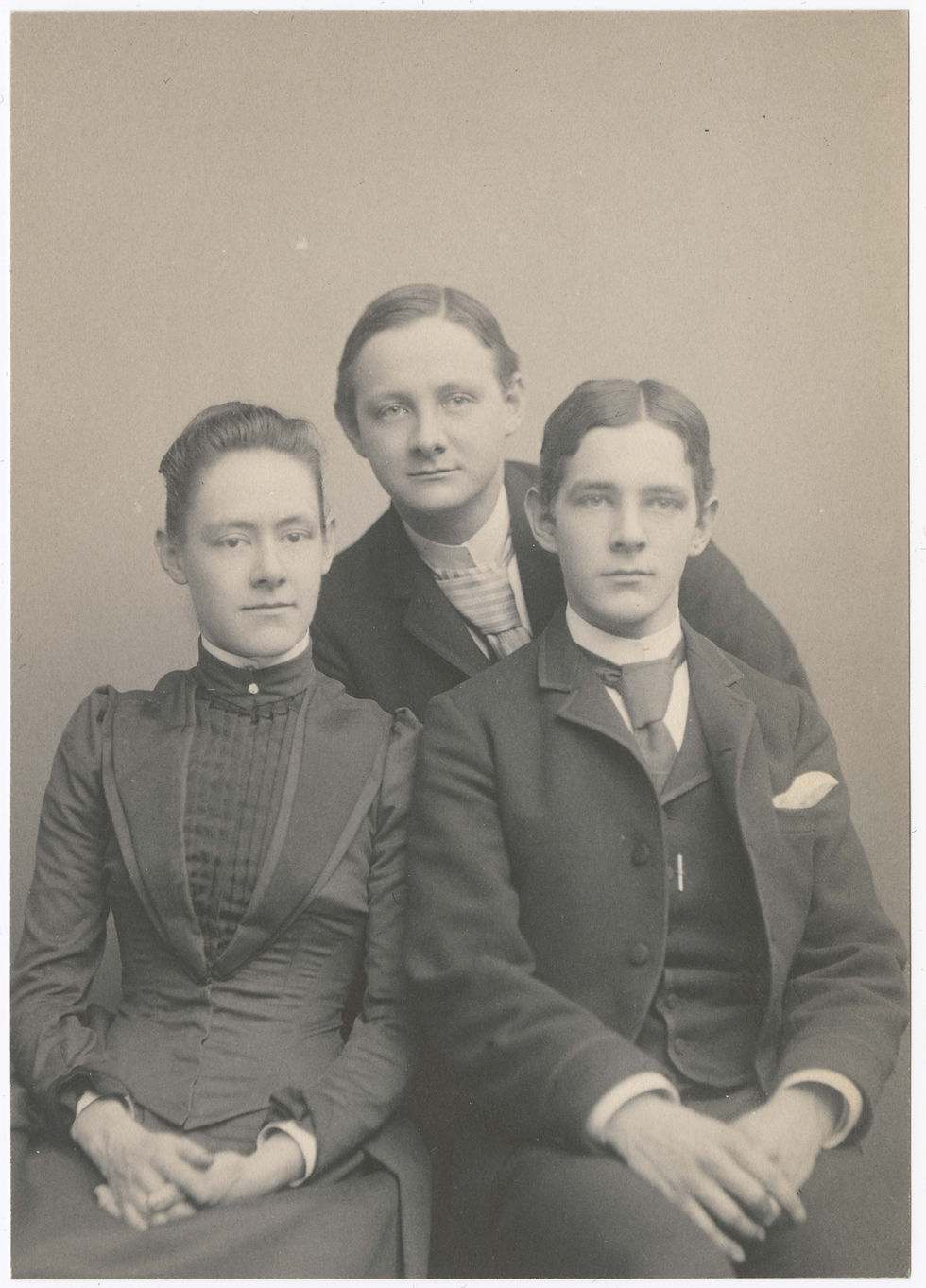

This photograph shows Leonard’s mother (Roseanne) and father (Harry) standing behind Leonard (right) and his little brother Ernest (left). Leonard was 4 years old when this photo was taken.

[Leacock family portrait], ca. 1908, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Leacock family fonds (V352/PA–24 and V352/PA-24 back)

Scarab and Mummy Lakes from summit of Pharaoh Peak, 1925-1931, Leonard Leacock/photographer, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies,

Leonard Leacock fonds (V353/I/B/PS–211)

[Cover of the Sky Line Trail bulletin],1940, Leonard Leacock/photographer,

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies (April 1940, Vol. VII, No. 26)

This photograph in the Sky Line Trail Bulletin of Leonard’s friend sitting on Pharaoh Peak was also featured in an issue of National Geographic in 1947.

In 1924 he moved to Calgary to work as a piano instructor and composer at Mount Royal’s Conservatory of Music, but the distance was not enough to keep him out of the mountains he loved so much (Leonard did not learn to drive until well into his sixties, so to get to Banff he had to take the train, a bus, or hitch a ride). He frequently stated in interviews that the hills and valleys surrounding Banff were like close personal friends to him and that being in the mountains was one of the great joys of his life.

While it’s likely that George X was taught (or at least shown) how to use a camera by his father or other family members, Leonard stated that he never received any kind of training on the subject. In one interview he admitted to being an amateur and simply learning through experience – Leonard could not remember a time in his life when he did not have a camera on hand.

Mount Ball and Shadow Lake, 1935, Leonard Leacock/photographer,

Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies (July1935, Vol. 2, No. 7)

[Cover of Trail Riders of the Canadian Rockies bulletin], 1934, Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies (October 1934, No. 37) George X was the president of the Trail Riders from 1934 – 1936 and was a life member alongside his mother and brother.

In 1931, Leonard completed the lantern slide lecture Sky-Line Trails of the Canadian Rockies, which featured photographs taken along the proposed route for the Banff-Jasper Highway – what is now the Icefield Parkway. It was on this trip that he took the Pharaoh Peak photograph featured by National Geographic. Leonard was a highly celebrated musician, receiving both the Alberta Achievement Award in 1972 and the Order of Canada in 1986 for his contributions to music; he never married. George X came from an extremely well-known and influential family of amateur photographers and he embraced changing technologies and created photos that weren’t strictly for use in the public sphere. He worked as an engineer and remained a life-long resident of Philadelphia, getting married and raising a family there. Leonard was a self-taught amateur photographer who explored photographic processes and created some content that was meant to be seen by audiences beyond his friends and family.

George X and Leonard were united by their love for the Canadian Rockies and their passion for capturing and sharing it through photography. Their amateur statuses did not lessen their talent nor their reputations and in fact seemed to free them to follow their own interests wherever they pleased. By pursuing what they loved they have created wonderfully diverse legacies that I, for one, am extremely grateful for and have thoroughly enjoyed exploring.

Comments